The Monthly Roundup: Nathan Ruser on scam centres and Starlink’s role

ASPI CTS Analyst Nathan Ruser on how Starlink is powering Myanmar’s scam economy—plus his must-reads.

This is a special edition of ASPI's Daily Cyber & Tech Digest, a newsletter that focuses on the topics we work on, including cybersecurity, critical technologies, foreign interference & disinformation. Sign up here.

Follow us on Bluesky, LinkedIn, or X.

Welcome to another edition of The Daily Cyber & Tech Digest Monthly Update! Each month, an ASPI expert shares their top news picks and provides their own take on one key story. This month, Nathan Ruser, Analyst in ASPI’s Cyber, Technology & Security Program, shares his perspective.

Starlink and Myanmar’s scam industry: resilience through connectivity

Earlier this month, ASPI released a report examining the rapidly growing scam industry in Myanmar and its role in the country’s wartime political economy. One of the trends briefly noted in that report was the rise of technologies that support and enable these scams, specifically the increasing reliance on Starlink to make scam centres more adaptable, resilient and effective.

In February this year, the Thai government attempted to crack down on scam compounds along its porous border with Myanmar. Authorities targeted the transnational infrastructure sustaining the centres, cutting off electricity from the Thai grid and restricting mobile and internet services from Thai towers.

This was a significant step, the first meaningful effort to weaken scam centres that conservatively earn tens of billions of dollars annually. But the barriers proved temporary. With the tacit permissiveness of Myanmar’s junta, operators quickly replaced Thai connectivity with Starlink terminals.

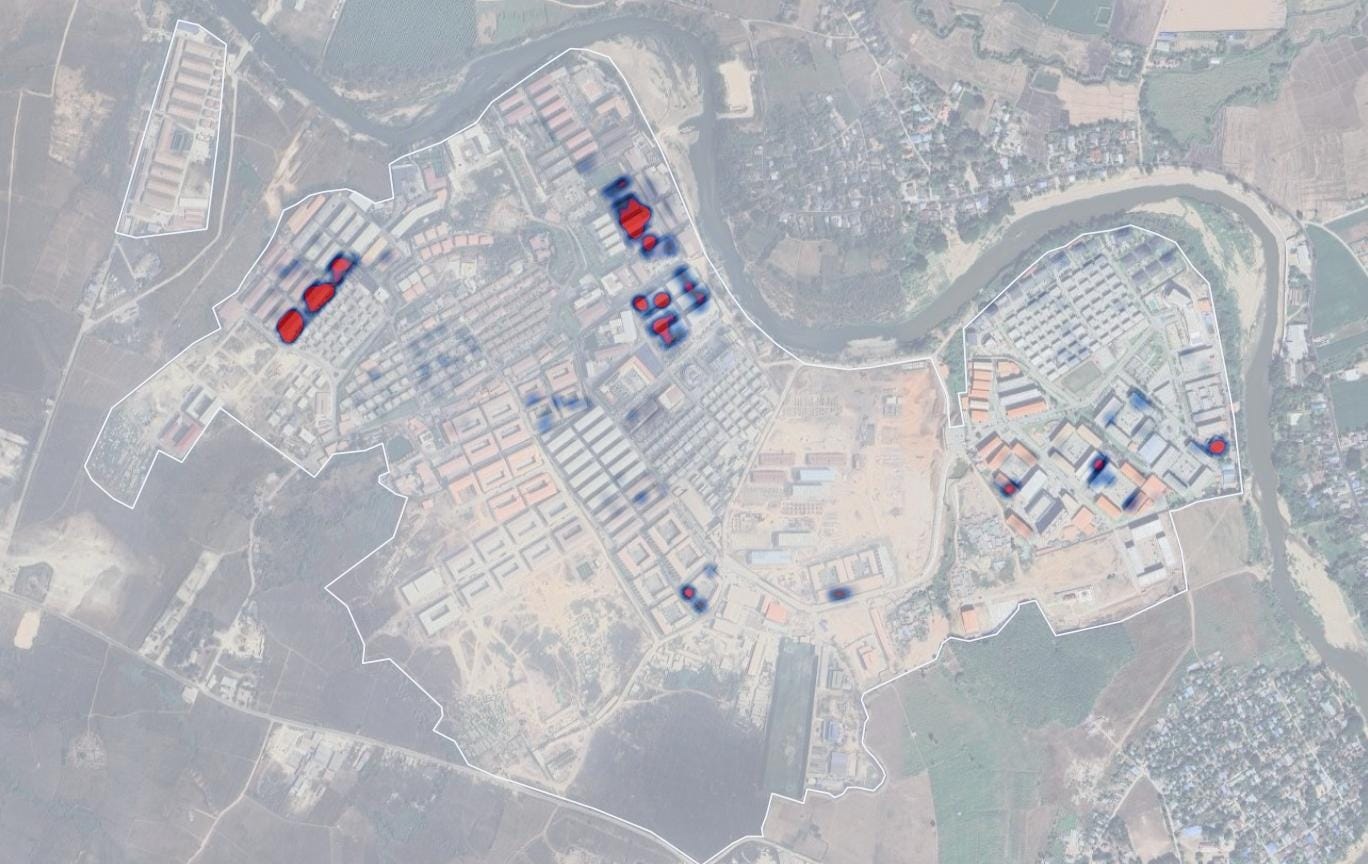

As the images below show, satellite imagery from 18 February, just two weeks after the crackdown, revealed more than 1,000 Starlink dishes on rooftops inside the KK Park scam complex. By May, Thai intelligence reports put the figure above 2,000. A heatmap of terminals across the site underscores just how concentrated and entrenched this connectivity has become.

Satellite imagery and heatmap show KK Park’s rapid reconnection to Starlink after Thai service cuts

Starlink spreads inland

As conflict and pressure push scam centres further inside Myanmar, Starlink use is accelerating. The image below shows around 100 terminals clustered around buildings in a compound in Lawksawk, 200km from the Thai border.

Starlink terminals clustered on rooftops in a Lawksawk scam compound.

Where once scam operations depended on Myanmar’s unreliable power and telecoms grid, Starlink and diesel generators now allow them to function almost anywhere. Every major Burmese city hosts thousands of small-scale scam centres that can thrive with just an empty office, a pool of desperate workers, armed guards, and reliable internet from Starlink.

The growing reliance on Starlink in Myanmar’s scam industry presents both challenges and opportunities. Starlink signals could be shared with law enforcement and governments to help detect emerging scam hotspots, complementing tools like mobile phone tracking. Since the 2021 coup, a permissive environment has allowed syndicates to expand into vast compounds devoted to online fraud. Yet these centres need little more than an office, vulnerable workers, guards, and Starlink’s reliable connectivity, making them easy to reproduce across Burmese cities.

Crackdowns, such as Thailand’s efforts along the border, rarely weaken the sector; they simply push it further into Myanmar. That makes Starlink itself a critical pressure point. The company has already demonstrated in Ukraine that it can geofence and disable terminals within specific areas. Doing so in Myanmar could have an immediate and global impact, disrupting the industry and sparing victims billions in losses each year.

Just as technology firms are expected to curb violent extremism or child exploitation on their platforms, they should extend that responsibility to scams. For policymakers with few levers to influence Myanmar’s conflict economy, Starlink offers one of the most direct tools available.

My must-reads

Reuters

Presented as a striking scroll-through comic, this investigation draws on months of interviews with nine people trafficked into scam centres in Myanmar between 2022 and 2025. Their consistent accounts trace journeys from Africa, South Asia and Southeast Asia into forced labour, exposing the role of purported immigration officials at Thai airports in facilitating trafficking. The format brings to life both the mechanics of recruitment and the brutal daily routine inside compounds that continue to thrive in Myanmar’s borderlands despite international crackdowns.

The Southeast Asia Public Policy Institute

This policy paper reviews national and regional responses, drawing on research, consultations with governments, industry, civil society and international organisations, and insights from the August 2025 ASEAN Scams Workshop. It identifies critical gaps in enforcement, highlights innovative measures already underway, and lays out recommendations for building a coordinated and resilient regional approach.

Tech for Good Institute

Scams exploit not just technical weaknesses but also human trust, behavioural habits and systemic vulnerabilities, eroding confidence and causing mounting losses across the region. This report argues for a whole-of-society response, drawing on consultations and roundtables with ASEAN stakeholders. It captures both the scale of the challenge and the urgency of strengthening collective defences as digital transformation accelerates.

For more on China's pressure campaign against Taiwan—including military threats, interference and cyber warfare, check out ASPI’s State of the Strait Weekly Digest.